Abstract

Collapse is not a singular event but a pattern within a pattern, emerging from the recursive nature of human attempts to manage complexity. Drawing from cybernetics and systems thinking, this article explores the deep patterns underlying civilizational breakdowns, where the feedback loops between economic strain, social organization, and environmental context become maladaptive. By considering the limits of learning and adaptation, it becomes evident that the diminishing returns on complexity are not merely technical problems but epistemological ones. The failure to recognize and manage the systemic relationships that constitute society invites not only decay but a dissolution of meaning itself.

Patterns of Patterns: The Fractals of Civilizational Decline

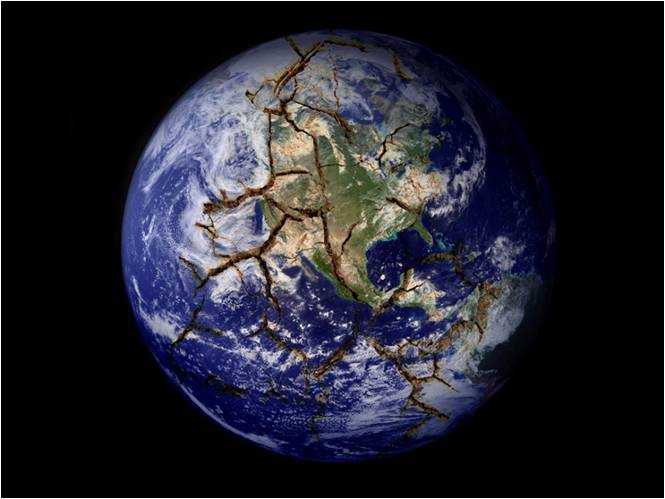

In tracing the fall of civilizations, we must begin by shifting our focus from the external signs—crumbling infrastructure, fractured institutions, or social unrest—to the underlying patterns that generate these phenomena. We are not dealing merely with a collection of discrete problems but with a network of interrelated processes that give rise to a pattern of breakdown, a polycrisis. The structure of collapse is recursive, not linear, and it emerges through the interplay of feedback loops that span economic, social, and ecological domains. To understand collapse, then, is to recognize the recursive patterns of human behavior that become maladaptive in the face of changing contexts. As societies grow, they develop increasingly elaborate forms of organization—bureaucracies, technologies, laws, and markets—that are designed to regulate and manage complexity. Yet, these very forms can become pathological when the relationships they are intended to govern begin to shift in ways that render old patterns of thought and action inadequate.

The Problem of Excessive Complexity: Misguided Learning in the Face of Change

A society’s attempt to solve problems by adding more layers of organization or technology is itself a kind of learning—a pattern of learning that seeks to absorb disturbances by increasing complexity. The Romans, for instance, constructed roads and fortifications to extend their reach; the Chinese built walls and expanded bureaucratic ranks to govern vast territories. Yet, each of these responses followed a similar pattern: they assumed that more control, more organization, or more resource extraction would solve the problem. But this assumption reveals a failure to appreciate the epistemological limits of complex systems.

As Gregory Bateson might argue, the more we attempt to control a system by adding to its complexity, the more we risk misunderstanding the relationships that compose it. For instance, increasing military spending to counter external threats may temporarily reduce anxiety but can also drain resources from more adaptive uses, creating vulnerabilities elsewhere in the system. The feedback loops become distorted; we lose track of what effects arise from our actions, as the symptoms we seek to manage proliferate and interact in unforeseen ways.

The Double Bind of Social Inequality and Fragmentation

Social stratification and the concentration of wealth and power present another pattern that recurs in collapsing societies. The elites, through the structures that serve their interests, may believe they are acting to stabilize the social order by suppressing dissent, hoarding resources, or maintaining status quo institutions. Yet, this response traps both the elites and the broader society in a double bind—an insoluble problem where every apparent solution reinforces the conditions that created the problem in the first place.

The more a society becomes stratified, the more rigid and brittle its social structure becomes. It loses flexibility because the channels through which it might receive and respond to feedback are constrained by hierarchical control. In this sense, inequality is not merely a moral issue but an epistemological one: it constrains the flow of information within the social system, leading to maladaptive responses that fail to recognize the interconnectedness of the whole. The suppression of dissent, for instance, may seem to quiet unrest, but it also blocks valuable feedback, creating a blindness that prevents timely adjustments.

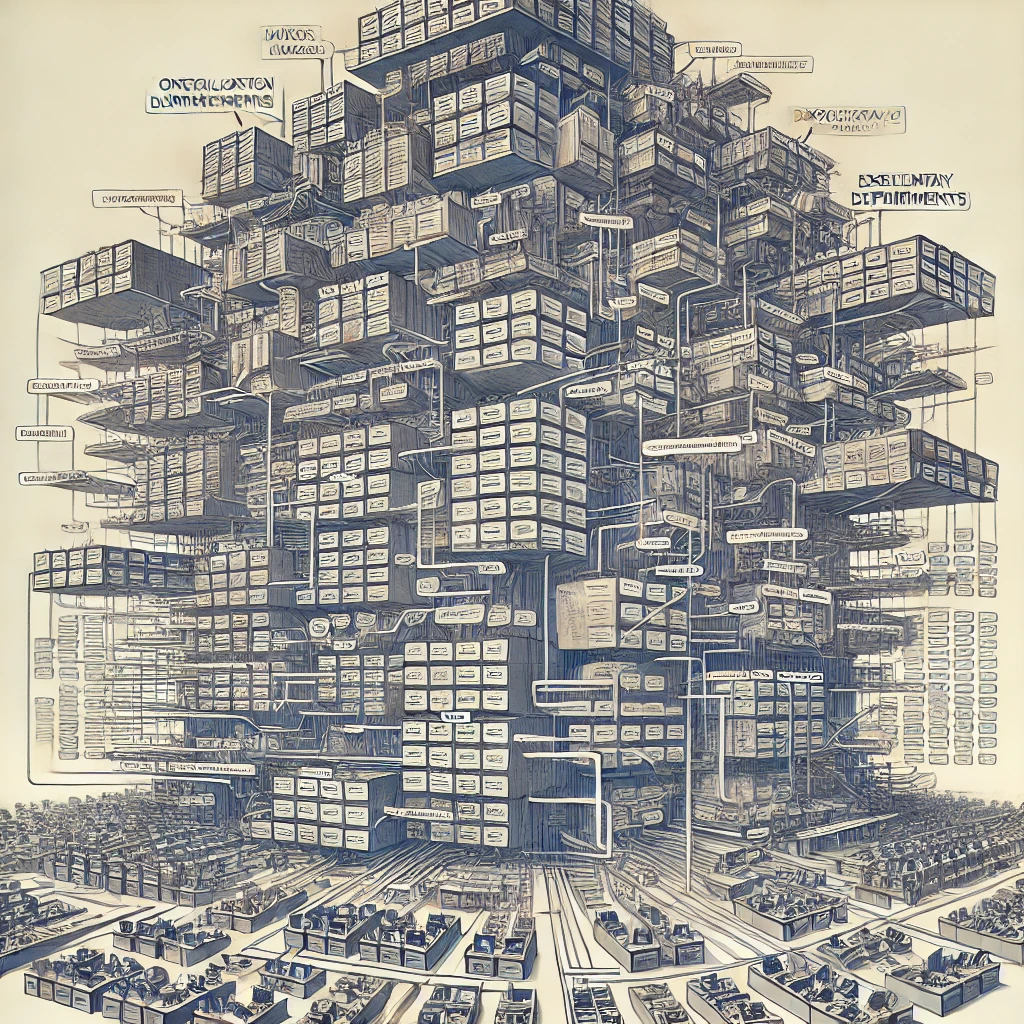

The Dance of Bureaucracy and Disorder: The Pathology of Administrative Expansion

Bureaucratic expansion is a recurrent pattern in civilizations facing the pressures of increasing scale. As the number of administrative layers grows, the feedback loops between decision-makers and the population they serve become longer and more distorted. Each new layer adds complexity, but not necessarily flexibility or responsiveness. It creates a form of informational noise, where signals about the actual state of affairs are filtered, delayed, or altered before reaching the decision-makers.

This is not merely a matter of inefficiency. It is a deeper problem of communication pathology within the social system. The signals that guide decision-making become saturated with redundancy and irrelevance, much like a poorly tuned feedback amplifier. The result is that the system responds not to the reality of the situation, but to an abstraction of it—an abstraction that grows ever more disconnected as more bureaucratic layers are added.

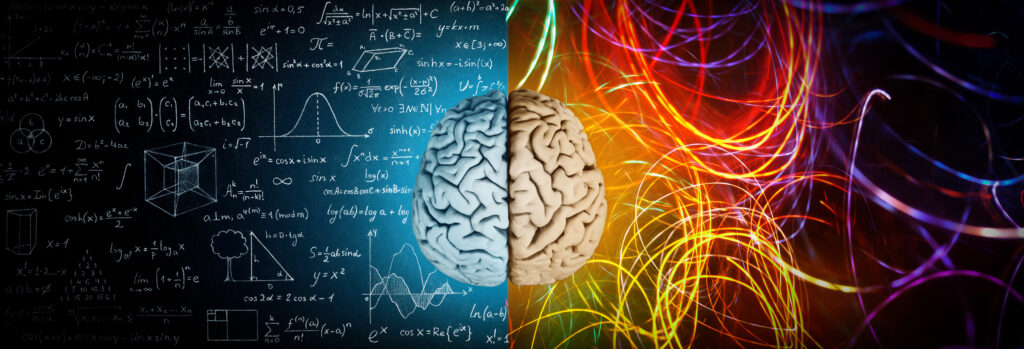

The Pathologies of Power and the Loss of Double Description

When we examine the collapse of societies, we often find a loss of what Bateson called “double description“—the ability to perceive reality through multiple, complementary perspectives. As societies become more rigid and hierarchical, they often lose the capacity for double description, favoring instead a single, dominant narrative that guides decision-making. This mono-perspectival approach excludes alternative viewpoints and adaptive strategies that might otherwise prevent collapse.

“The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think.“

In moments of crisis, a failure to maintain double description can lead to catastrophic decision-making. Consider the response of the Qing Dynasty to the Opium Wars, where a rigid adherence to traditional views on trade and foreign relations prevented the court from adapting to the realities of global power dynamics. Similarly, in the lead-up to the French Revolution, the ruling classes clung to the belief that their privileges were divinely sanctioned and immutable, unable to see the growing pressures that would soon overwhelm them.

The Ecology of Mind: Feedback, Adaptation, and the Limits of Control

Ultimately, the failure to manage civilizational complexity is a failure to recognize the ecological nature of human societies. In Batesonian terms, it is a failure of the “ecology of mind“—a breakdown in the feedback loops that constitute the learning processes of the social system. When societies treat problems as isolated issues rather than interrelated patterns, they lose the ability to adapt holistically. The symptoms may be economic, social, or environmental, but the underlying pathology is the same: a loss of flexibility, an inability to recognize feedback, and a persistence in maladaptive behaviors.

Consider how civilizations often respond to economic crises by increasing resource extraction or imposing austerity measures. These actions may temporarily alleviate symptoms but often exacerbate the underlying problems by further depleting natural and social capital. The over-exploitation of resources mirrors the over-exploitation of people—both reflect a pattern of misunderstanding the limits of the system. The feedback loops that should signal the need for change are ignored or suppressed, allowing maladaptive behaviors to persist until collapse is inevitable.

Subsidiarity: The Wisdom of Local Adaptation

In the dance between control and disorder, the principle of subsidiarity stands as a vital counterbalance against the pathology of excessive centralization. As Gregory Bateson might argue, systems thrive not through rigid hierarchies of command but through the distributed intelligence of their parts. Subsidiarity, in this sense, becomes an ecological principle—a recognition that adaptive capacity arises when decisions are made at the lowest possible level, closest to the context in which those decisions will take effect. Just as in a forest, where the health of each tree depends on its symbiotic relationships with the soil, fungi, and other trees, a healthy society depends on empowering local actors who can perceive and respond to the nuances of their environment.

When a society disregards subsidiarity in favor of top-down control, it risks creating informational bottlenecks and epistemological blind spots that distort feedback and inhibit learning. The more the center imposes uniform solutions from afar, the less it can sense the subtle shifts and local variations that signal the need for adaptation. Thus, the erosion of subsidiarity becomes not merely an administrative flaw but a systemic pathology—one that, if unchecked, propels the entire system toward rigidity, fragility, and ultimately, collapse.

Conclusion: Patterns of Learning, Unlearning, and Collapse

The collapse of civilizations, then, is not simply a consequence of external shocks or internal decay; it is a failure to learn from the patterns that constitute our own experience. It is a failure to adapt to the complexities of our environment in ways that preserve the flexibility of the system. The patterns of collapse are recursive, not linear—they emerge from the interactions between different levels of the system, from individual decisions to collective behavior.

If there is a lesson to be drawn from the recurrent patterns of civilizational collapse, it is this: we must cultivate an awareness of the recursive nature of our own actions and the limits of our knowledge. We must recognize that the systems we create to manage complexity can become maladaptive when they lose touch with the deeper patterns of feedback that guide learning. To avoid collapse is not merely to solve problems but to learn to see them as part of a larger dance—a dance of adaptation, unlearning, transformation and subsidiarity. In the words of Gregory Bateson, “The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think.” Our challenge is to align our thinking with the patterns of the living world, to learn not only from success but from the recursive patterns of our own failures. Only then can we hope to sustain our societies in the face of the complexities that lie ahead.

In Batesonian style, this article emphasizes the recursive and systemic nature of collapse, treating it not as a linear sequence of events but as a pattern that emerges from the dynamic interplay of feedback loops. It suggests that the failure to recognize and adapt to these patterns lies at the heart of civilizational decline, making collapse as much an epistemological problem as a structural one.